Connections

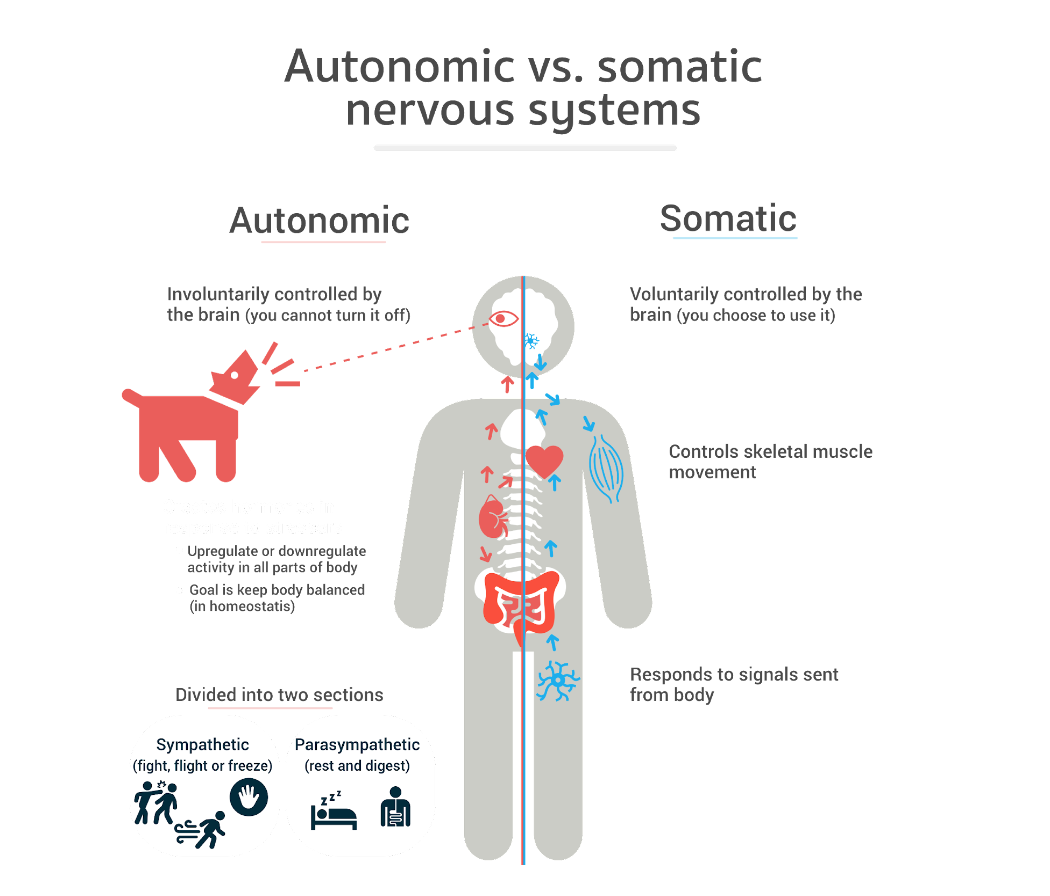

Stress response: The ANS plays an important role in the body’s reaction to stress. The sympathetic division initiates the “fight or flight” response. This response readies the body for action by boosting heart rate, releasing stress hormones such as adrenaline, and directing blood flow to vital organs. This response heightens alertness and improves chances of survival when faced with danger.

Heart rate and blood pressure: The ANS helps heart rate and blood pressure maintain their normal levels. In times of stress, the sympathetic division of the ANS increases heart rate and constricts blood vessels. While relaxed, the parasympathetic division of the ANS slows heart rate and promotes blood vessel dilation, encouraging a state of rest.

Digestion: The parasympathetic division of the ANS stimulates various digestive processes. It facilitates the secretion of digestive enzymes, promotes food movement through the gastrointestinal tract via peristalsis, and triggers the release of bile and pancreatic juices. The sympathetic division of the ANS acts as an inhibitory force on these processes. Its main task is to redirect blood flow to different parts of the body during periods of stress, inhibiting the digestion process.

Respiratory function: The ANS regulates the muscles responsible for respiration. This ensures that oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange in our bodies is properly facilitated. In times of stress or physical exertion, the sympathetic division is activated and can help increase the rate and depth of our breathing. During periods of relaxation, the parasympathetic division assists in slowing down our breathing.

Body temperature regulation: When faced with stress, the sympathetic division of the ANS is responsible for thermoregulation. It stimulates sweat production to promote heat loss and constricts blood vessels to conserve heat. When at rest, the parasympathetic division assists in regulating body temperature. It does this by adjusting blood flow and facilitating heat dissipation or conservation based on the body’s needs.

Urinary function: Within the ANS, the parasympathetic division plays a role in stimulating bladder contraction and relaxation of the urinary sphincter enabling voluntary urination. On the other hand, the sympathetic division can hinder bladder contraction and encourage urinary constriction. This can result in a temporary delay of urination, especially in stressful situations, or a frequent need to urinate due to tension in the bladder.

Movement efficiency: Fascia plays a significant role in enabling seamless and coordinated movement. It reduces friction between muscles allowing them to slide and glide over each other smoothly. This process facilitates the transmission of muscular forces during movement and improves efficiency by minimizing energy expenditure.

Force transmission: Fascia facilitates the transmission of forces produced by muscles. It distributes and transfers tension, leading to synchronized movement patterns and optimal force generation.

Protection: Fascia acts as a protective layer. It shields structures like muscles, nerves, and organs from potential harm caused by external impacts or injuries. Fascia’s cushioning effect absorbs and disperses mechanical forces. This diminishes damage to the underlying structures.

Joint stability: Fascia enhances joint stability by extending support to the neighboring muscles and ligaments. By upholding proper alignment and balance, it effectively decreases the chances of injury and helps maintain optimal joint health.

Proprioception: The fascial tissues contain sensory receptors called nociceptors. Nociceptors respond to mechanical forces and are essential for motor control, coordination, and body awareness.

Fluid dynamics: Fascia promotes the movement of vital fluids such as blood, lymphatic, and interstitial fluid. By transporting nutrients, oxygen molecules, and waste products throughout the body, this supportive function allows for optimal tissue health and strengthens the immune system.

Postural integrity: Fascia helps distribute body weight evenly. This helps prevent muscular imbalances and other postural abnormalities leading to mechanical dysfunction.

- Suarez-Rodriguez, V., Fede, C., Pirri, C., Petrelli, L., Loro-Ferrer, J. F., Rodriguez-Ruiz, D., De Caro, R., & Stecco, C. (2022, May 18). Fascial Innervation: A systematic review of the literature. MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/23/10/5674